Leigh and I met through writing, not cancer. We both had the same breast cancer – invasive lobular – but we got together initially because she wanted to chat about how to market some of the essays she was writing about her travels. I was a freelancing then and coaching writers a little. So Leigh got in touch. The cancer thing was just a funny coincidence.

Leigh was bright without trying to outshine anybody. Smart without being a show-off. That first time we met, I learned Leigh had done a “little” cycling, a “bit” of traveling; a “smidge” of political work back in Washington D.C. She didn’t really go into her accomplishments much; Leigh was humble. She casually mentioned bicycling alone through India at one point in the conversation. Later, I learned she broke her collar bone during the trip and just kept pedaling through the pain. That was sort of Leigh’s way.

As we chatted that first evening at the Triple Door, Leigh shared cocktail trivia (her favorite was called The Last Word and was served at her memorial) and the two of us went through our respective cancer histories. Who’d had what done; what kind of collateral damage was left behind. With cancer treatment, there is always damage. Leigh had lymphedema, a side effect of her breast cancer surgery and already knew a ton about it. She knew you had to tackle it immediately; you had to get a compression sleeve and a gauntlet, a glove. She was already wearing both, completely on top of the issue mere months out of treatment.

Later, Leigh pretty much threw down the gauntlet when it came to lobular breast cancer.

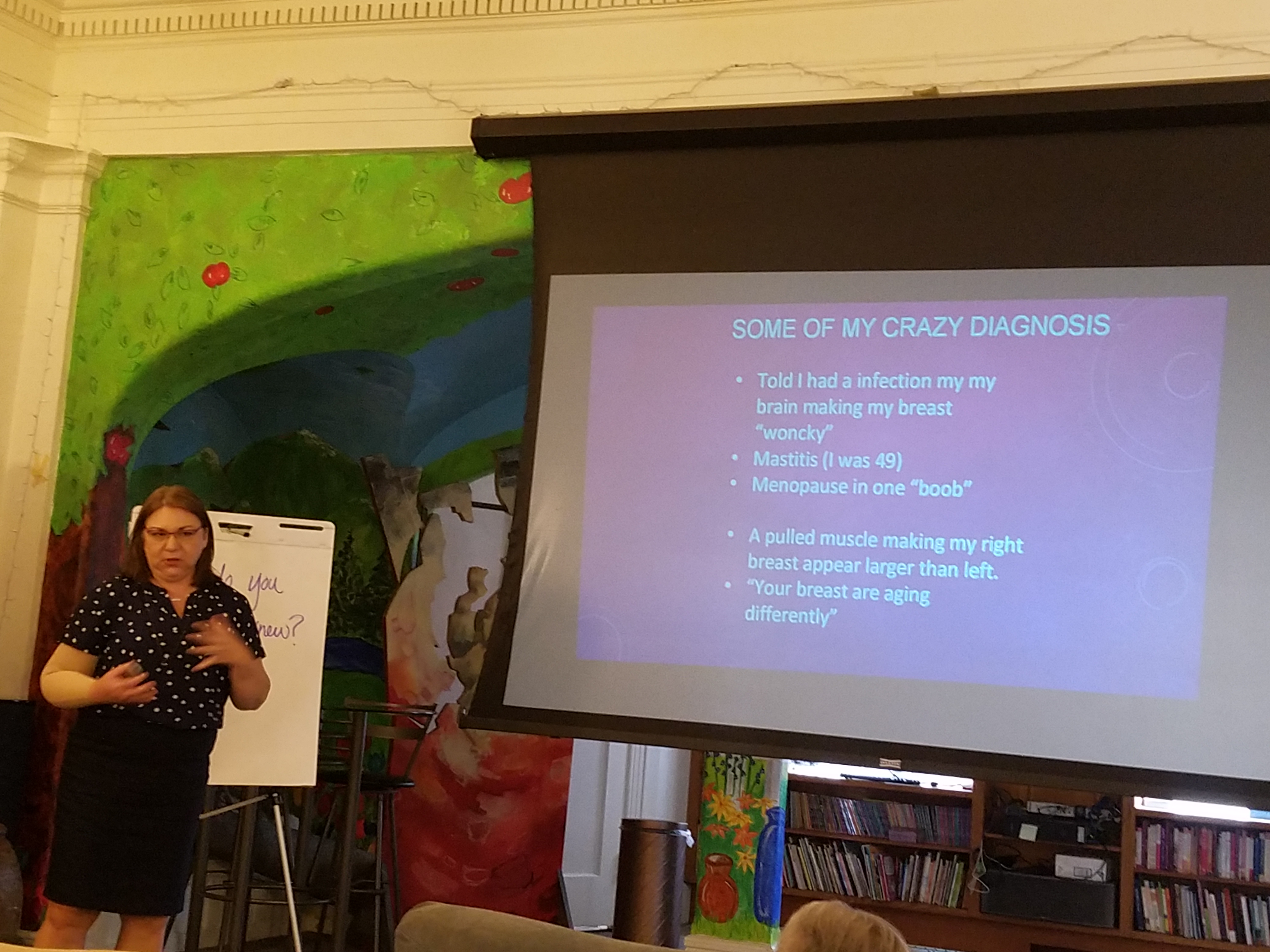

Our subtype was supposedly “rare,” she told me that night, yet lobular BCs make up 10 to 15% of all breast cancers. Leigh had already dug into the stats and found them wanting. She told me Google had to correct her when she tried to look up her “globular” breast cancer. She’d never heard of it; I’d never heard of it. None of the other lobular patients Leigh had already connected with had heard of it.

Despite all those awareness campaign and news articles and research studies over the years, it was Leigh who recognized there was a huge gap in knowledge and education regarding lobular BC (and lymphedema); she identified a gaping hole where scientific research on this subtype needed to be. She was already amassing information in her calm, clear-eyed and absolutely fearless way.

Leigh and I hit it off that night. As much as I loathe cancer’s war metaphors, it felt like we were in the same trench. We were both single and straight; neither of us had kids – that we knew of, anyway (sorry, old joke). We both lived alone. And of course there was the cancer thing. Little by little, Leigh and I became friends and eventually partners in the fight against the crime of cancer.

Leigh was the most humble person I’ve ever met. And now that she’s gone … How horrible, how bitterly painful it is to write those words … And now that she’s gone, I see clearly that she was even more accomplished, more modest, more unpretentious and generous than I ever realized. Since her death a month ago, I’ve been reading and listening to tributes from her many friends, learning more and more of her incredible accomplishments – the awards and accolades; the spectacular summits and cycling trips; the political campaigns and come-from-behind victories.

Later, there would be scientific meetings and white papers and a nonprofit, the Lobular Breast Cancer Alliance, a sustained collaboration of ILC patients, clinicians and researchers that Leigh basically conjured up out of thin air. There were many others who helped – Dr. Steffi Oesterreich, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, a slew of patient advocates and scientists. But Leigh was the visionary, the dreamer with the calm, at times even calculating, patience and diplomacy to – I don’t know – move a mountain.

Or something equally difficult: get cancer researchers to listen to cancer patients. Leigh not only got them to listen. She inspired them to switch gears, to lean into lobular. As one of the scientists who attended her memorial said, “Leigh Pate changed my life.”

Leigh changed many lives. She saved lives.

Cancer patients are inherently selfish. We have to be to stay alive. We have to focus on our treatments, our side effects, our pain, our complications, our worries and fears. As a cancer patient, you continually have to advocate for yourself. And Leigh advocated for herself. But Leigh was not selfish. She advocated for others, always. Individually and at a larger societal level. Sometimes, she even advocated for others when she herself was in pain, was dealing with complications – an infection or a blood clot or one of the other unpleasant things she had to deal with at the end. Leigh took unsolicited phone calls from scared strangers who’d just been diagnosed; she patiently answered people’s questions and soothed their fears, never letting on to many what she was dealing with herself. Most people in the lobular breast cancer world didn’t even know she’d been diagnosed with a second primary and that it was aggressive and advanced from the get-go. She didn’t necessarily want them to know. She didn’t want to confuse the issue, muddy the waters: it wasn’t about her or her health, she would tell me, it was about getting the word out about lobular.

Leigh did all the things to get rid of that second primary cancer. She went through the surgeries, tried the chemos, even enrolled in a CAR-T immunotherapy trial, everything. But this particular cancer – Fallopian tube/ovarian, also understudied – was too much even for her, even as strong as she was. Leigh seemed to know this, but she kept moving forward anyway. Just keep pedaling, right? She lined up specialists to help her with the complications that arose from treatment even as she sent out encouragement to post-docs and promoted new findings in lobular research through social media. She continued to advocate for herself and for others to the very end. Her last tweets were about a lobular conference taking place in The Netherlands and how excited she was about the research and collaborations that would spring from it. Leigh was generous. And seemingly indefatigable.

And now she is gone.

To say that Leigh Pate will be missed is practically a criminal understatement. Many will miss her, even people she’d never met will miss her. I miss her already. Her thoughtful guidance and sly wit, her big brain and her bigger heart. I miss her fairness, her sense of integrity, her ethics, her humility. Leigh never needed to take up all the oxygen in the room to satisfy her ego; she didn’t care about accolades, she cared about people. She always was ready to help and how she actually knew how to help. Leigh knew how to get shit done. And she got a lot done in her calm steadfast way.

So yes, I will miss those green glasses, that great smile. That inner strength and serenity. I will miss Leigh’s sense of humor, her sense of justice. Her fierce independence and fiercer loyalty. Her patience because I’m afraid I have none. I still can’t believe she’s gone. My only consolation is seeing the good she left behind. Feeling the love. Hearing those accolades, as much as Leigh would roll her eyes. My only solace is thinking (hoping, praying) she’s off on her greatest adventure yet, pedaling, pedaling, pedaling into a never-setting sun.

For those who want to continue her legacy: There have been at least three memorial funds set up in Leigh’s honor, including a BCRF (Breast Cancer Research Foundation) fund which will go toward lobular research. Here’s a link to that: https://give.bcrf.org/fundraiser/4014139

Memorial donations can also be directed to The Lobular Breast Cancer Alliance Leigh Pate Memorial Advocacy Fund, lobularbreastcancer.org, or mailed to LBCA, PO Box 200, White Horse Beach, MA 02381.

Finally, Leigh received a lot of support from The Clearity Foundation and requested that memorial contributions be directed to them at www.clearityfoundation.org.

Ever get a question that sticks with you, that you can’t shake, that you keep ruminating on until you finally get an answer? My niggling question came in via email in the summer of 2015. The person emailing had just read a story I’d written the year before, shortly after I started working at Fred Hutch as a science writer and cancer whisperer. It was called

Ever get a question that sticks with you, that you can’t shake, that you keep ruminating on until you finally get an answer? My niggling question came in via email in the summer of 2015. The person emailing had just read a story I’d written the year before, shortly after I started working at Fred Hutch as a science writer and cancer whisperer. It was called

I guess I’m writing this post for them. I want people in the cancer community to to know there’s been some progress. The NCI is actively working to bring the SEER registry and its infrastructure into the 21st century so we can finally address these burning cancer questions – and who knows, maybe stumble onto a therapeutic insight or three.

I guess I’m writing this post for them. I want people in the cancer community to to know there’s been some progress. The NCI is actively working to bring the SEER registry and its infrastructure into the 21st century so we can finally address these burning cancer questions – and who knows, maybe stumble onto a therapeutic insight or three.

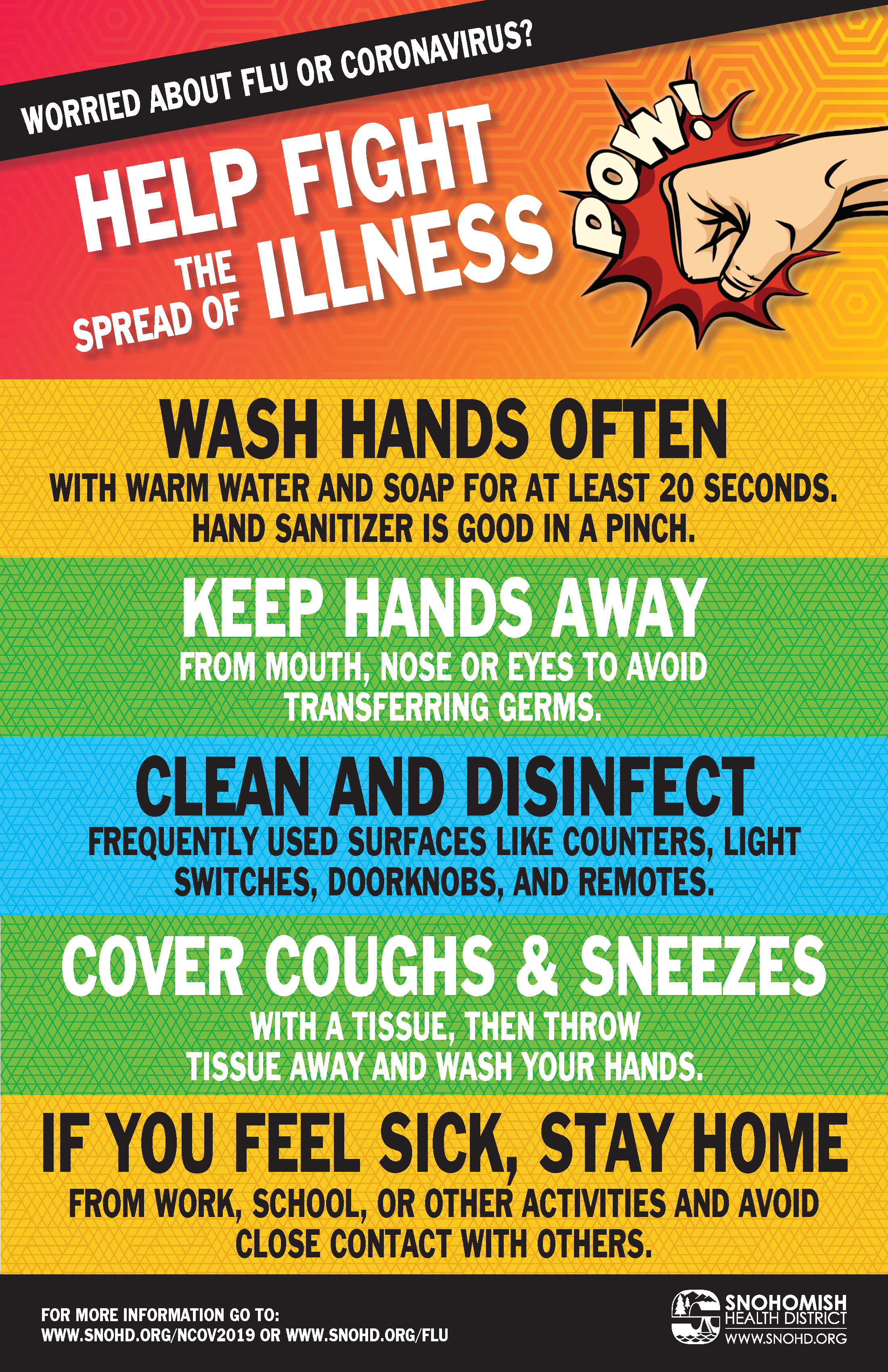

So now there’s a pandemic. And my workplace and our scientists are right in the thick of it. I interviewed a couple of friends and

So now there’s a pandemic. And my workplace and our scientists are right in the thick of it. I interviewed a couple of friends and

Last but not least, I celebrated (angrily acknowledged?) the eighth anniversary of my double mastectomy this week. Incredible that I have made it

Last but not least, I celebrated (angrily acknowledged?) the eighth anniversary of my double mastectomy this week. Incredible that I have made it

Discovered a new Twitter tool that I’m geeking out about a little. It’s called ‘Moments’ and it lets you string a bunch of tweets together — yours and others’ — to create a short story. It’s a bit like Storify, which recently lost its battle with cancer … er … capitalism. RIP, brave fighter! ; )

Discovered a new Twitter tool that I’m geeking out about a little. It’s called ‘Moments’ and it lets you string a bunch of tweets together — yours and others’ — to create a short story. It’s a bit like Storify, which recently lost its battle with cancer … er … capitalism. RIP, brave fighter! ; )

Here’s my

Here’s my